- Home

- Ross Lockhart

The Book of Cthulhu 2 Page 15

The Book of Cthulhu 2 Read online

Page 15

The size of a city, the creature yet bore some kinship with the lava-borne larvae. In its wake, the mountainous isopod left glowing opals which bored into the splintered earth like depth charges, like the treasures carelessly spilled by a god, or the eggs sown by a devil.

There are no gods, as you mean it, Sergei interrupted. There are those who dwell outside, and who neither live nor die, as we know of life and death. They answer prayers, but only when offered in blood and geometry, and their miracles…

But if they’re not gods, then they can be stopped.

Stopped! This is their world. It always was, and will be again. They do not seek our extinction, but only to hasten the day when the world will be ripe for their dominion, and His awakening. They redraw the faultlines of the ocean floor to drive the continents back beneath the waves, and raise the Pacific seamounts to the sky, as it was when they came down from the stars.

But it’s not their world, it’s ours! We’ll destroy them, or send them back where they came from—

If you could but see them, you would know how insane that is. And why should you care? In two thousand years, their plans will bear fruit. In two hundred years, the ice caps will melt, the ocean will rise and drown all human cities, anyway. But this is not their concern—

Ingrid ripped free of Sergei and fled away across the shattered abyssal plain, back to the bottomless pits. Diving into an octagonal well, she made her focus into a sword that slashed at the darkness. Before she could find anything upon which to practice her attack, something found her, and seized her in talons of icy, paralyzing pain.

A gargantuan humanoid form reached up out of the pit with mammoth forelimbs cloaked in crawling, viscous flesh, and unfurled vast black wings or outsized dorsal fins that effortlessly beat back the lead-dense water.

Trapped and suddenly feeling as corporeal as she was helpless, she cried out.

Sergei answered, instantly beside her as always, yet even he trembled in fear before her captor. See! he raved. Behold what we hoped to destroy, and what you hope to plunder, and what will bury us all!

It stretched out to nearly fill the vast pit, yet only the roughest outline of its titanic form could be picked out of the darkness, for its body was festooned with crinoids, clams and tubeworm colonies. So glacially slow and deliberate were its movements, that life thrived on it undisturbed; and yet now, it flew faster than she could perceive to draw her bodiless ghost up to its inscrutable, luminous eyes.

A rugose, boneless sac bearded with restless coiling tentacles, the creature’s head was an octopoid of obscenely magnified proportions. There was no escaping those clutching, prescient tentacles, or the piercing gaze of its hideously lambent eyes, which seemed to turn her mind inside out.

For all its awesome size and unfathomable intelligence, the godlike monster seemed to retreat into a fugue for an age of endless moments, until some decision was made.

What does it want? she demanded.

Suddenly, the colossal prodigy bombarded her with convoluted psychic hymns. It sang to her of One older and more terrible than all its kind beneath the sea, the One who slept until the world was perfect, and of the rapture of His imminent return.

I am most disturbed to report, Sergei numbly sent, that it wishes to… what is your word…? Negotiate.

What could such a creature want from her, that it could not simply take? Ingrid retreated into the innermost bolthole of herself and pulled the cerebral dirt in after her, but the psychic onslaught only redoubled as it sought to crush her with understanding.

What do they want?

They want to share their knowledge with the human race. For your benefit and theirs.

Why would they do this?

The power to harness the fire of the earth’s core… they want you to have it. They have come to understand only dimly how quick, how fragile, is the human mind, but how devastating the effects of its tiny genius. In human hands, that power will hasten their ends a hundredfold.

But why? Who would have given them such an idea?

I believe you did, my dear…

Ingrid feigned shock and let herself seem dead, until the tentacles and talons relaxed their grip. She pulled away and forced herself to visualize her body, miles above her, lying prone on the table in the holding cell on the research ship.

She willed herself across that distance instantly, as she would will herself out of a nightmare. For in the end, that was all this was. Sergei was a master manipulator. Somehow, he got inside the minds of his mercenary captors and drove three of them to suicide. Surely, he was trying to do the same to her, but she was not so powerless.

She opened her eyes, and the cell, dingy and too brightly lit, surrounded her. Her body hung heavy from her exhausted mind, an exquisite assembly of dead weight that trembled when she sought to draw in a breath of fresh air.

Her hands lay on the table, trapped in the scarred, stained hands of Sergei Lyubyenko. His eyes floated up behind drooping lids, regarding her with empty, bloodshot orbs.

Her arms dangled from her shoulders like concrete counterweights with the cables cut. She struggled to make her body move, to sever the contact from her that seemed to hold her still, that yet trapped a part of her beneath the sea.

Abruptly, Sergei’s eyes opened impossibly wide and stared at her. An eerie, yellow-green light kindled within them and ate through the cornea and iris, spreading until his slack, waxen face gleamed like a torch blazed within it.

“I will negotiate with your masters now,” he said, with no trace of an accent, no scintilla of humanity.

Ingrid fought to free herself. She raked his hands with her nails and hurled herself back in her chair to sprawl across the uncarpeted steel floor. Sergei made no move to pursue her, but repeated his demand in the same flat, untenanted tone, as he shuffled towards the door.

Ingrid had to stop him. She had to get to Mankiw first, and try to make him understand what they would be dealing with.

Her head boiled with the opening salvo of a five-alarm migraine. Her body resisted her best efforts to climb to her feet. The door swayed and rocked before her, but she was resolute, even if her body was not.

Blood dripped from both her nostrils, and her muscles began to ache, then to tear themselves apart. Her bowels and bladder explosively evacuated and swelling bubbles of pure agony erupted in her belly and chest and every muscle, in the marrow of her bones, and the pressurized cage of her skull.

She screamed, but she could hear only the teapot whistle of compressed gases pouring out of her burst eardrums, her tear ducts and sinuses, forcing its way out of her pores.

It made no difference that she had been sitting at the table with Sergei the entire time, or even if the entire jaunt was only a dream or a telepathic fantasy. The mind plays tricks, Sergei had said, and he was not lying.

The agony of explosive decompression swept aside all doubts and points of debate and devoured her whole. And still, she tried to stop them. Still, she tried to beat Sergei to the door.

She almost made it.

Her outstretched hands were blue-black with burst capillaries and liquefied muscle tissue. The steel mirror on the back of the sealed hatch showed her only a shapeless red collage, doubly filtered through the blood flooding her eyeballs. Her tongue swelled to fill her mouth and block her throat, but her brain exploded out her eye sockets before she could drown on the briny tide of her own fluids.

Ingrid flew away, taking the only escape left to her—out of her body and down into the dark to claim a sleek new body. And this time, she felt no fear, for she was going home.

•

“Once More, from the Top . . .”

A. Scott Glancy

“This is the fourth time,” the old man grumbled, shifting his gaze out the window to the sparsely planted grounds of the VA hospital. “How many more times do we have to go through this?”

“Just a couple more, Sergeant Hennessey,” said Levine, stooping to plug the power cord into the cracked and

yellowed wall socket. “Your memory being what it is, we need to go through this as many times as possible. You added some details the second and third times through. Maybe you’ll remember something more this time.” As Levine busied himself with the camera, his partner, Henry Parker, unpacked the files and laid them out on the card table in front of Sergeant Hennessey, like he was dealing out a game of solitaire.

Hennessey angrily gripped the arms of his wheelchair with trembling hands. “It’s been seventy years! That’s more years than the both of you and ‘Sambo’ stacked together. You can’t know what it’s like trying to remember that far back.”

“You’re right about that,” Levine said as he laid his jacket over the back of a folding chair and loosened his tie. The staff kept the veterans’ hospital uncomfortably warm. But, that’s why people retire to Florida, Levine thought. To warm their bones. “Of course, some things are harder to forget than others.”

“Seventy years,” Hennessey sighed as he ran a gnarled hand over his snow-white hair. “Why the hell is the Navy interested again after seventy years?”

“They didn’t tell us,” Levine lied as he sighted the video camera on Hennessey and hit the record button. “‘Need-to-know’ means they don’t need us to know.” Levine checked to see that the camera was running and then took his seat across the table from Hennessey. “After a lifetime in the Marine Corps, you must’ve learned that if you’re not cleared for the answer, don’t ask the question.”

“I suppose,” Hennessey said, eyeing the pair of men as they settled into their seats and continued unpacking their files. Levine, the younger of the two, was thin, with glasses like an accountant and fingers like a pianist. As part of his cover, Levine had cut his hair to military regulation for this op, but he figured Hennessey could tell he wasn’t really Navy. Levine was a civilian from his scuffed shoes to his J.C. Penney suit. Parker, on the other hand, was military to the bone, thick-featured and barrel-chested, his ebony scalp cleanly shaven, but nonetheless a “landlubber.” If he was getting steamed about Hennessey calling him “Sambo,” he wasn’t showing it.

As he pulled out his notepad and pen, Levine could feel Hennessey dissecting them with his eyes, trying to figure out what they were really up to and who’d really sent them. Being kept in the dark was grating to Hennessey. Levine supposed it was almost ironic. Seventy years ago Hennessey and the rest of the 3rd Battalion walked into a small town in Massachusetts without a clue as to what they were facing. Somewhere up the chain of command somebody, probably someone who hadn’t joined Hennessey and his fellow Marines on their little excursion, made the decision that the guys on the ground just weren’t cleared to know what was going on. And here they were, seventy years later, debriefing Hennessey about a mission he never learned the particulars about and lying to him about who was asking the questions. The more things change, the more they remain the same.

Of course, thought Levine, if those men had told the truth, told Hennessey and the other Marines what was waiting in those rotting piles of moldy stone, he never would have believed them. But if he had…if he had believed the unbelievable, he would have deserted before ever setting foot in Innsmouth. Levine wondered what Hennessey would do if he knew the truth about why he and Parker were there.

“So? Ready to begin?” Levine asked without much enthusiasm.

“Ready?” Hennessey spit back. “Ready to dredge up the worst fucking night of my entire life? Ready to get the shakes and not be able to keep down the swill they serve here or even close my eyes all night ’cuz if I do I’ll be right back there in the middle of it all killing those things in the snow?” Hennessey tried his best to rivet the two of them with a withering stare. It may have worked on Marine recruits forty years ago, but it had lost much of its power since then.

Embarrassed and resigned, Levine quickly glanced to Parker. Parker remained as inscrutable as one of those Easter Island statues. With no apparent support from Parker, Levine answered weakly, “Uh, yeah.”

Hennessey rolled his eyes. He bowed his head to pinch the bridge of his nose, as if warding off an impending migraine. “Sure,” he mumbled. “Of course. Let’s get to it then.”

“When did you first get wind that your battalion was being tasked for something special?” asked Levine.

Hennessey shifted uncomfortably in his wheelchair. “We knew something was up when the entire battalion was assembled in Punta Gorda. Companies and platoons that were dispersed all over the country chasing Sandino were suddenly called back to the coast and immediately herded onto a Navy transport. Everyone knew the big brass had something in mind. Rumor was, even the Colonel didn’t know.”

Levine scribbled a few notes. “Do you remember the ship’s name?”

“No. I told you that the last time. I thought Jews were supposed to be smart.”

“I’m not Jewish,” Levine said without looking up from his notes. Levine figured it was the only way the old bastard could get back at the two of them for making him go through the story over and over again. Since he couldn’t intimidate them, he would suffice with insults.

“Yeah. Next you’re going to tell me he ain’t a nigger either.” Hennessey laughed mirthlessly. One again, Parker didn’t even blink. Something in Parker’s poker face told Levine the big man was thinking, ‘I bet you’re going to die soon, old man.’

“Where were you first briefed on the details of the Innsmouth operation?”

“The Boston Naval Annex; the same day our ship docked.”

“And that day was?” Levine volleyed.

“It was February 23rd, 1928. They marched the entire battalion into a warehouse in the Annex and sat us down on these wooden benches. There were already about a hundred guys in suits in there, T-men we were told, and nearly a dozen Navy officers in their faggoty dress whites. They had this big map of the town and all the approaches. Plus a screen set up for the movie and slides they showed later.”

“Do you remember the name of the operation? What was it code-named?” Levine interrupted.

“Just what I told you before,” Hennessey said irritably. “It was something biblical, like Project Moses, or Pharisees, or something. Y’know, Old Testament.”

“And who gave the briefing?” Levine prodded.

“There was a Captain from Naval Intelligence and a T-man. I got the impression he was Secret Service. I don’t remember their names ’cuz I never saw ’em again. There was one fella, though, I seen plenty of since.”

“We know,” interrupted Levine. “You already mentioned Hoover.”

Hennessey glared at Levine and leaned forward onto the table. “Are you going to let me tell the damn story or not?”

“Sorry,” said Levine, leaning back to keep the distance between them. “Please continue.” Levine felt a flush of embarrassment at the clumsiness of his questions. He was an Elint Specialist, not an interrogator. Listen in while the Kremlin orders out for pizza? No problem. But interrogation? And Parker? As far as Levine could figure, he was some DOD mechanic currently on loan to the Company. If this was the best debriefing team Alphonse could put together, it meant that either this was a low priority op, or things at Delta Green were well and truly fucked.

“‘Military support for civilian law enforcement’ he called us,” Hennessey hissed. “But the operation the brass laid out was more like the kind of thing we’d been doing for United Fruit in Nicaragua.”

“What exactly had you been doing for United Fruit?” asked Parker.

“Whatever we were told to do,” Hennessey snapped, glaring angrily at Parker’s interruption. But Hennessy’s watery eyes couldn’t hold Parker’s cold stare and he quickly looked down to his own trembling, knotted hands. After a second, Hennessey cleared his throat and looked up. “’Bout the same thing our boys did in Vietnam. ’Cept we didn’t have TV cameras breathing down our necks. We’d move into a pueblo that our officers said was supporting Sandino, round all the spics up, shoot those that gave us any trouble, burn the corn and rice in the fi

eld, torch the huts, and march everyone out to a ‘controlled area’ where they couldn’t support Sandino. ’Course, often as not those same corn fields would be turned into banana plantations by the next time we marched through, but what the hell did we care. It ain’t changed much since ’27 as far as I can see.”

“The film,” said Levine.

“Huh?”

“Could you tell us again about the film they showed you.” Levine had not only undone his tie, but also rolled up his sleeves. He could feel the sweat in his armpits and around his collar. Parker, however, didn’t spill a drop—lotsa jungle work.

“Did I leave that out? Well, there was some film shot from an airplane. It showed the town and the surrounding countryside. The captain described the main features of the town, pointing out this road and that. The last part of the film showed a small, black, rocky island, or maybe it was the top of a reef poking out of the sea. But they stopped the film before that got too far along. The captain acted like it was something we weren’t supposed to see.

“Then there were the slides. Someone, probably one of Hoover’s boys, had wandered through town with a hidden camera in a suitcase. The shots weren’t very well aimed and most were out of focus. The camera must’ve been hid real good and run real quiet because some of the locals were awful close when he snapped the shutter. One just about looked right in the camera lens. When that blotchy, goggle-eyed face flashed onto the screen, I guess I must’ve gasped along with everybody else. Everybody except Paskow, of course. Fucker’s heart pumped ice water.

“But that face…it was like something out of Lon Chaney’s makeup kit. The head was all wrong. During Korea I saw a kid in Seoul with the same kind of head. ‘Water Heads’ they’re called. The skull was somehow soft and bloated-looking. The guy’s eyes were bulging and watery, and even though it was just a still shot, those eyes seemed not to have any lids. That’s when I knew this was going to be worse than anything I could imagine.”

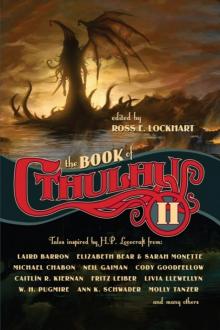

The Book of Cthulhu 2

The Book of Cthulhu 2